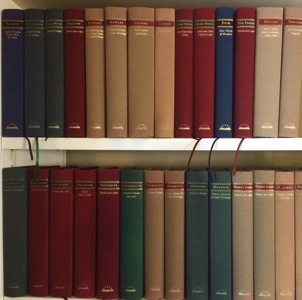

A year and a half ago, my uncle Chuck died unexpectedly. My family wanted me to have his books because I was a reader like he had been, and I was also a writer. And I wanted the books, especially his Library of America books, which looked so lovely and uniform and canonical. More importantly, I wanted to continue the conversation we’d been having since I’d learned to read—the “what are you reading,” conversation—because we were both always reading something. We were insatiable. We understood this about each other. There were so many things I would miss about him, but I knew I would miss this conversation the most.

There were about two hundred Library of America books, and my family wanted me to take them all. My home is small. The bookshelves are in my small living room. My inheritance of books was a mixture of boon and responsibility and onslaught. I found a spot for another bookshelf behind the couch. I went through the Library of America books and chose the ones I thought I was most likely to read, all fiction. I stored the other half (George Washington’s diaries and the like) in my mom’s attic. She rarely offers attic space, but she knew I couldn’t stand the alternative just then.

Read more at Ploughshares.